Paul Monk MA PhD is a polymath and widely known as a public intellectual. After completing his PhD in International Relations, looking at cognitive and policy aspects of US counter-insurgency operations during the Cold War, he worked for a number of years in Australia’s Defence Intelligence Organisation on East Asia, with a particular emphasis on the challenge of North Korea, the stagnation of Japan and the rise of China.

Dr Monk spoke to CAUSINDY’s Nick Fabbri:

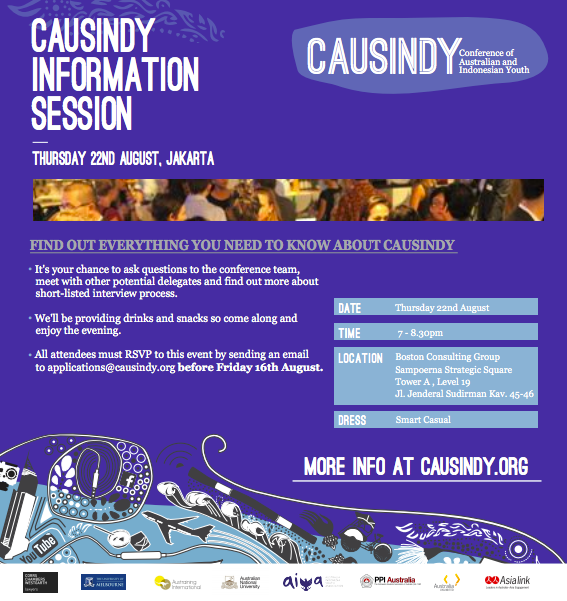

NF: I’m here with Dr Paul Monk who is a doctor in international relations and a former senior intelligence officer with the defence intelligence organisation and a director at Austhink Consulting. We are here this morning to talk about Australia and Indonesia and how CAUSINDY, the Conference of Australian and Indonesian Youth, can contribute to that relationship positively. Dr Paul Monk it is a pleasure to be with you this morning.

PM: Good morning Nick.

NF: Can you perhaps start by briefly outlining some of the key challenges facing the Australia-Indonesia relationship, and ultimately where you feel the relationship can go from here over the next 10, 20, 30 years?

That’s a great deal and I’ll try and put it in a brief context. I think it’s important to frame where we might head in the context of where we have come from. There are a number of landmarks in the bilateral relationship going back 70 years which seem to be neatly and more firmly embedded in the public understanding. That goes all the way back to when the Indonesian nationalists after the Second World War struck out for independence. Australia had to make a decision. Do we back the Dutch going back to resume their colonial rule, or do we back the nationalists?

We decided to back the nationalists. That was a step based on the perception that colonialism was going to pass away, and that we wanted an effective relationship with this new and emerging nation. We found over the next 20 years that it was very difficult to forge that relationship with the new Indonesia in the way we’d hoped for, because it had a leader in Sukarno who had rather, how would you say, dictatorial tendencies. He had designs on wider territories which caused tension with his neighbours. And so there were a number of instances in which we were on the wrong side of Sukarno. The most notable instance or turning point in the development of the relationship was when he indicated that Dutch New Guinea should be a part of Indonesia. Not because its inhabitants were the same ethnic group of cultural background as the Javanese, but because the Dutch had ruled it. Australia opposed that idea, but Washington and London made clear that they thought the tidiest solution here in terms of regional development was to let Sukarno have it and not make an issue of it. We were very uncomfortable with that but had little choice but to acquiesce in it.

It has remained a subject of some tension. As everybody knows similar things occurred with East Timor a decade on. But in between there had been a major change within Indonesia, which is when Sukarno was overthrown and along with him the Indonesian Communist Party which had been the object of great misgivings within Indonesia and Australia and around the world. It was destroyed in a concerted purge by Suharto and the military in Indonesia. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed extra-judicially; it was a very brutal business. But instead of that causing misgivings in Canberra, the process was seen as reassuring. We were close to Suharto, deeply relieved the communist party had been destroyed, and nobody really to this day has reckoned with the enormous human cost and bloodshed that was entailed

The relationship with Indonesia from a diplomatic point of view came better under Suharto than under Sukarno. But from a public point of view there was discomfort with Suharto because he was a dictator and because of the bloodshed that occurred when he took power. Notwithstanding, there were a series of points over the next 20 years with Suharto in which Canberra had to decide ‘do we confront Indonesia, disagree with it, or try to build the relationship?’ The consistent policy has been to try and build that bilateral relationship. It hasn’t been easy, but that’s been the focus from the Department of Foreign Affairs and by and large from the military, against the background of concern and unease in difference.

Over the past decade things have moved forward rather well, and the primary reason for that is that Suharto fell from power with the Asian Financial Crisis, and there was a democratic transition in Indonesia. It’s not altogether surprising that we’ve found it easier to deal with a democratic government because it is more open. It allows more scope for debate with Indonesia, and can read it more easily. We are not faced with a single power centre that’s easily offended.

To then go to your question about where are the tensions or the uncertainties in the relationship right now, well clearly one of them is to do with boat people, refugees transiting Indonesia to get to Australia. They don’t want to settle in Indonesia, they want to get here. We would prefer that we didn’t have so many coming, but when we send them as Jakarta recently pointed out, if Tony Abbott comes into power and he turns back boats to Indonesia that’s not appropriate because the boats did not come from Indonesia they came by Indonesia.

You are a firm believer in the importance of looking back on this historical perspective and to have a firm understanding of our history as both Australia and Indonesia in order to tackle these problems in the bilateral relationship. It’s not something we can just be completely prospective about, we have to be retrospective in looking at where we’ve come from.

Yes I think so, and we need to be dispassionate in our view of our shared history as far as we can. Indonesia was an emerging state, there was no Indonesia before the late 1940s, and so it had to grow into statehood. We were a very different nation state, with a long British background and a stable government, and the differences between the two countries were enormous. We had many advantages they didn’t have so many; they spoke a completely different language had a different culture etc. There were many obvious ways in that there could have been misunderstandings or disagreements. What is remarkable is that despite those things, over time we have managed to keep deep hostilities from getting entrenched and we’ve now entered a period where there are deliberate and constructive efforts to deepen the relationship. It’s not a matter of remembering grievances or animosities from the past, but a matter of actually understanding the sources of tension and disagreement.

How do you see the current bilateral engagement at the political, economic, business and public policy level?

At the public level there is significantly less tension or hostility towards Indonesia now than there has been at any time since the 1940s. I think the reason for that as I remarked before is that we now have a democratic government in Indonesia that is substantially more open than any government Indonesia has had since independence. That means more Australians can observe it and think, well there is debate going on there, there are changes in policy and differences of opinion. We’re more at ease with that. As for how we’re conducting the bilateral relationship, it seems to me that at the declaratory level with things like the Asian Century White Paper largely wave hands and say ‘Indonesia’s a big country with a substantial and growing economy and we hope that it continues to grow and we need to grow with it’. That’s all very general and rhetorical. I don’t see many signs at the top of the tree that there is deep engagement and sophistication.

But at the level of what’s often called second track dialogue there are some very encouraging signs. I think the CAUSINDY youth dialogue fits into that context very well. I think in many ways that’s the best way for it to proceed, in that it filters up to people who are not specialists in Indonesia and who are very busy, but who can then get a sense in private briefings and meetings that there is lots of stuff going on and there’s a kind of subtle micro-political movement or micro-diplomatic movement going on.

CAUSINDY the Conference of Australian and Indonesian Youth is an example of that second track dialogue that will filter through society over the next couple of generations given that 50% of the Indonesian population is below the age of 35 and that demographic is who we’re bringing to our conference in Canberra. Could you speak to the importance of investing in the youth of both Indonesia and Australia in ensuring that there is that cohesiveness and integration on a personal level?

I think it’s going to be difficult for either government to invest across the board. For example as we said a few years ago that we should get Indonesian language into many if not all of our schools. I’m not sure that’s a practical proposition for a number of reasons. There are impediments to mass take up to a language that culturally and linguistically is very different from our own. So I think what we need is targeted, more strategically orientated cultivation of these skills.

We need language programs that encourage people with an aptitude for language to pick up Indonesian or Chinese and run with it. Rather than have programs where a lot of resources are expended in dropping everybody into them where the great multitude don’t have an aptitude for the language, can’t figure out why they’re being made to learn this, and drop out fairly quickly. That’ll take some sophistication. I don’t see at the moment that the government in Canberra has their mind around that problem, which is why I remarked that the Asian Century White Paper is a hand wave. It talks in very generic terms about language learning, but nothing substantive is being done about it.

In a recent speech Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono challenged the global perception that Islam and democracy were incompatible. Is Indonesia therefore an example of a southeast Asian nation balancing modernisation, Islam and democracy?

It’s increasingly looking as though it can. From its inception, Indonesia had a majority Muslim population and there was a long period of time in its development where the question was ‘which interest group or ideological group will dominate?’ There was the military, there was the communist party, and there were the Muslims. From a western point of view, there was unease about a Muslim state or a communist state. There was a tendency to hope that Sukarno could keep the balance between them, but then he was a difficult guy to deal with. So when Suharto took over and said ‘we’ve got a new order and we will keep that balance, and it’s the military that will hold it,’ there was considerable relief, but difficulty in dealing with a military dictatorship. Now we have a democratic society, it is not a theocratic one, it doesn’t seem to trending in that direction and it is certainly not a communist one.

It is important for us to bear in mind, however, that Indonesia does have a distinctive brand of Islam, broadly speaking, and a brand of Islam that is easier for us to engage with than many Middle Eastern and North African varieties. It will nevertheless take a great deal of work for us to feel really at ease with that and rather than say that Islam is or is not compatible with democracy, we should say that Islam needs to grow into a modern and democratic context, just as Christianity had to. Let’s bear in mind that for most of western history we had monarchies and dictatorships often of a deeply reactionary nature, which were also Christian. Did that mean that Christianity was incompatible with democracy? Well in its traditional and hierarchical form yes it was. But we still have a great many people who are Christians and we still tend to think of western civilisation as Christian civilisation and we have democracies. What we need to see is a similar development in the Islamic world, and that’s going to take some time and work.

Final Thoughts:

Many years ago when I was the age of the young people who are embarking on this dialogue, I spoke to a professor of international law from Boston and we kicked around my interests in the world and what I hoped to do. And he said to me, and it was an important point, ‘young man, do you see yourself in the world of ideas as a priest of an explorer?’ and I said ‘an explorer, every time’. And he said, ‘well, have I got the course for you’. So here’s what I would say to the young delegates from Australia or Indonesia. Ask yourselves when it comes to the world of ideas and exploring the relationship do you see yourself as a priest or a mullah on one hand, or an explorer on the other. I hope the answer in both cases will be an explorer. There is a lot of exploring to do, to open up new territory and to build new bridges, and that’s the future we should all embark on.’